Moonglow on the surface of it is a memoir of a dying man, his life as a businessman, his tender love for his wife even though she was mentally fragile and needed institutionalisation, his love for his stepdaughter whom he adored and who reciprocated it lovingly in his final days and his obsessive passion for the space mission. In the Acknowledgements too Chabon mentions a list of names adding “if they existed, would have been instrumental to the completion of this work”.

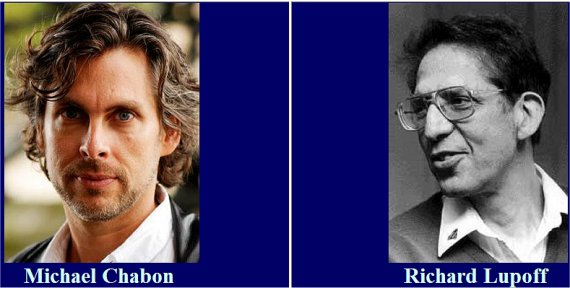

Wherever liberties have been taken with names, dates, places, events, and conversations, or with the identities, motivations, and interrelationships of family members and historical personages, the reader is assured that they have been taken with due abandon. In preparing this memoir, I have stuck to facts except when facts refused to conform with memory, narrative purpose, or the truth as I prefer to understand it. The “Author’s Note” in the preliminary pages of Moonglow are revelatory. And this fantastical achronological landscape is only in the first few pages of this extraordinarily crafted story. It is quite a heady mix.īy page 45 of the book the grandfather’s reminiscences have included his meeting with a “hermaphrodite”, blowing up a bridge during World War II, meeting the founder of CIA - Wild Bill Donovan, a walk-on part of Russian spy Alger Hiss, introducing the character of Wernher Von Braun - brains of the nuclear missile technology V2 and later known as father of space programme, free love, Carmellite nuns in Lille, an unwed mother, a grandfather who had trained as a piano tuner and tried killing his boss, a rabbi who ultimately gave up religion to become a professional hustler. As the narrator, Mike Chabon, says that he heard about 90% of his grandfather’s life in the last few days. The nameless grandfather has bone cancer and is on a cocktail of drugs to keep him comfortable in his last days. Michael Chabon’s Moonglow is a story that is based on a series of conversations the narrator has with his dying grandfather. Apart from so-called hard science fiction, which he read ( as with The Magic Mountain ) for its artful packaging of big ideas, my grandfather regarded most fiction as a “bunch of baloney.” He thought reading novels was a waste of time more profitably spent on nonfiction. ( p.248)

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)